When beginners throw inside breaks they often struggle to lead the receiver, regularly throwing it a full yard or more behind the cut. Even with more experienced throwers, you still see vastly more turnovers caused by putting the disc on the receiver’s back shoulder than you would see on the open side.

Why is that?

What I think occurs is related to the how the situation changes when you pivot. Imagine first that you’re the thrower, standing square to the play – not yet committed (pivoted) either to forehand or backhand – and that the receiver is on the open side.

You’ll make your initial judgement on whether to throw based in part on how much separation the cutter has, how long it will take the disc to arrive, how close to the defender the disc would have to pass to get there, and how difficult it is to lead the receiver. (N.B. it’s very easy to lead a receiver who is running towards you or away at a very shallow angle, but increasingly hard to lead someone running more directly away from you.)

You might think that the throwing decision would be based on an estimate of how the situation will look at the time the disc is actually released, rather than how it looks to the thrower right now. And, of course, it should. But surprisingly, for many throws, you might not have to worry too much about that.

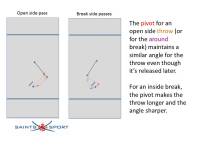

When you pivot out to the open side, the receiver’s movement (in the time it took you to step out) has probably changed the angle of the throw slightly more in the defender’s favour, and made leading the receiver slightly harder – but your step will improve the angle and make the situation more similar to your original perspective.  Similarly, you will have moved towards the receiver, making the throw shorter than it was when you originally perceived an opportunity to throw – so even though the receiver has moved in the meantime, you might still end up getting the disc to them in roughly the same place you originally intended.

Similarly, you will have moved towards the receiver, making the throw shorter than it was when you originally perceived an opportunity to throw – so even though the receiver has moved in the meantime, you might still end up getting the disc to them in roughly the same place you originally intended.

Time has passed, your viewpoint has moved, and yet the situation is likely to remain broadly similar overall.

For an around break, you’re also pivoting towards the side of the field where you’re going to throw, so something comparable applies.

But for an inside break, you’re commonly pivoting away from the direction you’re throwing. Everything changes. The throw might become longer than when you made your original assessment. The angle is sharper, taking the disc nearer to the defender and making it harder to lead the receiver. (Click on the diagram to enlarge.)

The effects of the time delay between your decision and your throw are no longer counteracted by your movement – rather, they are exacerbated. What your subconscious decided was a sensible throwing decision is now looking very different.

I think that’s a large part of the problem. The issue of the delay between decision and release barely arises on most throws, because any changes come close to cancelling out – the movement of the players downfield makes things harder, but your movement makes things slightly easier. So your subconscious – parsimonious as ever – ignores the problem.

As a quick and dirty heuristic, basing decisions on what you see now – rather than worrying about what things will look like when you’ve completed the throwing motion – is quite successful.

But for those inside breaks, suddenly the delay is a huge problem. Your movement has made the throw longer, and the angle sharper; the movement of the receiver has probably done the same thing. And – worse still – the fact that your throw is now longer actually means the receiver will have moved even farther by the time the disc arrives, which makes the throw longer, the angle even sharper, and so on ad infinitum. Zeno would have claimed the inside break was logically impossible 😉 – though he was wrong, of course, and the apparently infinite series does sum in practice.

It’s a vicious circle of increasing difficulty. And you failed to take this into account when making your original assessment of the throw. You might need to pull out at the last second, or – particularly if a beginner – you’re likely to throw it dangerously behind the receiver.

What can be done? You can’t ‘solve’ it, in some ways, as it’s an inherent problem caused by stepping away from the direction of the throw. But you can train the brain to deal with it, to allow for it, by putting some thought into your drills and your training. Even with complete beginners, who are perhaps doing only simple drills – with no force – based on throwing to a moving target, you might consider introducing that ‘opposite’ pivot early on, before their brain has learnt to get away with the easy option.

And knowing why these errors happen can make it that much easier to keep your temper when a few of your beginners just don’t seem to ‘get it’ after numerous attempts…

The way we attempted to ‘solve’ this at Fire last year was as follows, and has a lot to do with the process of faking.

The thrower should keep these principles in mind:

a) You want to gain yards towards the goal

b) Throws should be early (therefore with less angle) to achieve point a

c) Completion rate goes up if you move the force out of the way

d) Faking early achieves points c and b

So in a world where we value the breakside, and have cuts set up to get the disc there, throwers should be looking for this situation early, and start to fake and create space expectantly.

I think teaching beginners about being proactive instead of reactive ‘creates’ more time for these type of throws, and the situation in the diagram with the tight angle is less likely to occur.

LikeLike

Pingback: Wednesday Dumps: Ultimate Thanksgiving, Beau Smackdown, Chain vs. Revolver | Skyd Magazine

Very good observation about why this can occur! Yet another reason to make sure throwers engage the marker and ‘own’ their throwing space. This jives well with my thoughts on breakmark positioning throwing angles here: http://www.pulleddisc.com/skill-wow-5-intro-to-breakmark-angles/ (plug). I hadn’t thought of the issue you raise here…very well thought out.

LikeLike

When Fury was being coached by Bob Pallares (1998-2004), there was an explicit “rule” that you weren’t supposed to throw “across your body” inside-outs. Precisely because the difficulty of a throw increases so much as soon as the angle between your pivot and throw becomes less than ~90 degrees (as is illustrated in your diagram).

Fury’s rule was not a moratorium on IO throws, it just meant that the team was trained to use IOs to only hit cutters in certain places–and never where an around throw could work instead. In your diagram, both an IO and around can be used to reach the same space. Instead, a more risk-averse offense would have the targets for an around throw and IO throw be very different parts of a cutter’s path. There was an IO window of opportunity and then an around window of opportunity.

LikeLike

The effect of the mark is also important for understanding the difference between around and I/O. If a mark pressures an around, the thrower throws it farther to the outside, leading the cutter further, which is fine as long as the throw floats and makes it more difficult for a correctly positioned defender to get a block. But when a mark pressures the I/O, the thrower throws it farther to the open side, putting it behind the cutter and closer to the defender.

Our team talks about getting the I/O “waiting in the space” so that even if it’s pressured back towards the open side, it’s still in front of the receiver. It means that we look off tight, fast I/O breaks that other teams might take, but I think the percentages work out well for us.

LikeLike